The lord and important retainers would have sat at the north end of the hall, and in the centre of the building was a large open hearth. Doors at the north end led to the lord’s private apartments, whilst at the south end there was access to a separate kitchen above an undercoft (John of Gaunt’s cellar), where ale, wine and food would have been stored.

- Richard III was the last king of the House of York and the Plantagenet dynasty as well as the last English king to be killed in battle

- The search for Richard III began on 25 August 2012, the 527th anniversary of the king’s burial

- Richard III is reburied in Leicester Cathedral, less than 100m from where he was originally buried in the Grey Friars church

The king under the car park

In August 2012, during an archaeological excavation in a Leicester City Council car park a remarkable discovery was made: the skeletal remains of King Richard III. The blend of dark historical deeds and modern detective work captured peoples’ imaginations around the world and re-wrote the history of a much-maligned monarch whose grave had been lost for over 500 years.

There is an enduring interest in King Richard III, who reigned from 1483-1485. He is probably England’s most controversial medieval monarch; he was the last king of the House of York and the Plantagenet dynasty (which ruled England for over 300 years); and the last English king to be killed in battle.

The life of Richard III

Richard Plantagenet was born on 2 October 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire. He was the seventh and youngest child to survive infancy of Richard, Duke of York and his wife, Cecily Neville.

Only a few years after Richard was born the First Battle of St Albans took place in 1455. This battle marked the start of the ‘Wars of the Roses’ conflict between the ruling Lancastrian dynasty of Henry VI and the House of York led by Richard, Duke of York.

When King Edward IV was crowned in 1461, he gave his younger brother Richard the title of Duke of Gloucester. Richard spent some of his childhood at Middleham Castle, Yorkshire, owned by his cousin the Earl of Warwick. As Richard grew up he loyally supported his brother, the king, and was rewarded with further titles and roles including admiral, High Sheriff of Cumberland, Governor of the North, Constable of England, Chief Justice of North Wales, Chief Steward and Chamberlain of Wales, Great Chamberlain and Lord High Admiral of England.

On 9 April 1483 Edward IV died and his eldest son, the Prince of Wales, became King Edward V. At the age of only 12 Edward was too young to rule and a protector (regent) was required. The late King’s will had nominated Richard as Lord Protector, but Edward V’s mother, Elizabeth Woodville, resisted this appointment. After a few months of factional manoeuvring that resulted in arrests and executions of Elizabeth’s supporters, Edward V and his younger brother, Richard, Duke of York, found themselves under the care of their uncle, Richard, in the Tower of London. On 22 June 1483 a sermon was preached declaring that Edward V and his brother were illegitimate and that Richard should be king. A few days later on 26 June, Richard was declared King Richard III and he was crowned in Westminster Abbey on 6 July.

The Battle of Bosworth

Richard III’s reign was short, lasting just over two years. His nephews soon disappeared from sight and contemporaries came to believe that they were dead. Opposition to Richard’s rule grew, coalescing around Henry Tudor, the last Lancastrian claimant to the throne (then exiled in France). By 1484 the king was increasingly reliant on a small group of associates and the threat of an uprising against him overshadowed his reign.

Finally, in 1485, the long-awaited invasion occurred and Richard successfully forced a confrontation with the rebels near the town of Market Bosworth in Leicestershire. Having spent a night in Leicester at the Blue Boar Inn, Richard marched out across the Bow Bridge to confront Henry’s army. On 22 August, Richard’s greater force met Henry Tudor’s army in battle in what would become a pivotal moment in English history. Richard was slain, and his death brought to a close thirty years of bloody civil war, leaving Henry victorious as King Henry VII, the first monarch of the Tudor dynasty which would rule England for the next 118 years.

The road to the car park

After the battle, Richard’s body was carried to Leicester where a community of Franciscan (‘grey’) friars buried him in their friary church. Half a century later, the friary closed and was dismantled during Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. The king’s grave remained marked into the 17th century but eventually disappeared, and by the Victorian period it was widely believed that the body had been dug up and thrown into the River Soar.

In the 20th century, historians Charles Billson and David Baldwin started to cast doubt on this popular story but it wasn’t until 2011 when Philippa Langley of the Richard III Society approached the University of Leicester, that plans were drawn up to excavate the Grey Friars site and possibly locate King Richard’s grave.

Digging for Richard

On 25 August 2012, a digger broke the tarmac of the car park and a team of archaeologists led by Richard Buckley and Mathew Morris began the task of locating the actual friary.

The first trench revealed evidence of medieval buildings – possibly parts of the friary – and a human burial represented by pair of leg bones. Further trenches uncovered more of the friary, providing clues to the layout of the buildings and the location of the friary church. Soon it was realised that the human remains found in the first trench lay under the church choir where King Richard was reportedly buried. The Ministry of Justice issued a licence for the University of Leicester Archaeological Society to exhume the burial and osteologist Jo Appleby painstakingly uncovered the skeleton, which had an S-shaped spine.

The bones, bearing obvious battle wounds, were carefully recorded, exhumed and transported to the University of Leicester for further study.

Identifying a lost king

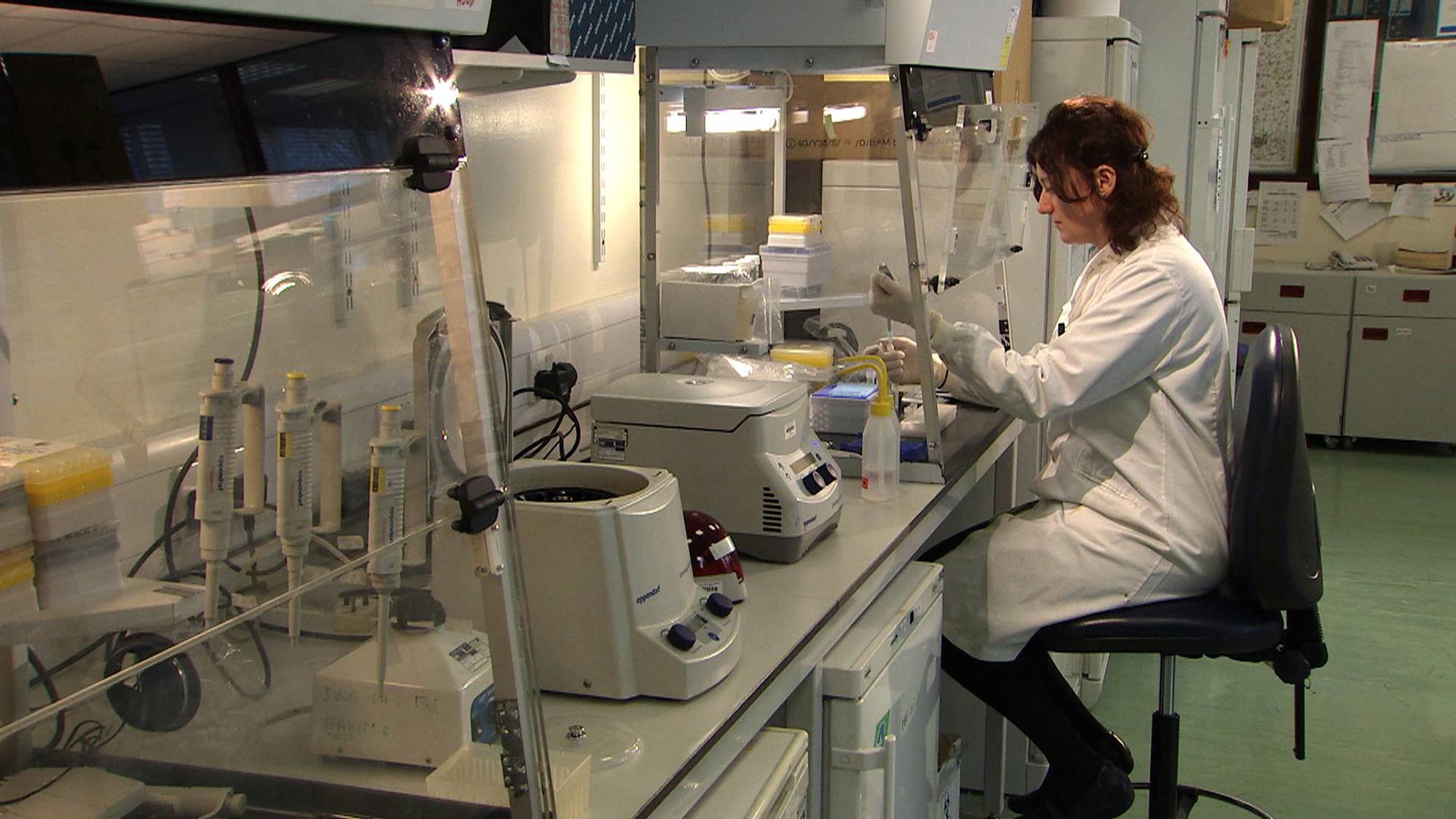

Using a combination of archaeological, historical, forensic, genealogical and DNA evidence, the conclusion of these studies showed that the skeleton was a male aged 30-34 who had sustained multiple battle injuries. He had died between 1455 and 1540 and was buried in the choir of the Grey Friars church with minimal reverence. Other evidence included spinal abnormalities (scoliosis). Crucially, the skeleton had a genetic match with known relatives on the female side of Richard’s family.

Dr John Ashdown Hill, building on earlier work, importantly identified the Ibsen family as being female-line relatives of Richard III. Professor Kevin Schürer set out to confirm the family link and to find another individual who could act as a comparator. The Professor and his team confirmed the skeleton’s mitochondrial DNA was matched with two female-line relatives of Richard III, the king’s 16x great-nephew Michael Ibsen and 18x great-niece Wendy Duldig.

Closing the case…

Analysis of the combined evidence led to the announcement in February 2013, at a packed press conference, that “It is the academic conclusion of the University of Leicester that the individual exhumed in September 2012 is indeed King Richard III.”

Richard III’s legacy in Leicester

Richard III is indelibly etched into the city’s fabric. Roads, schools and pubs are all named after him, whilst memorials and statues have honoured his memory since the 17th century. Thousands of people turned out to watch his reinterment in 2015 and today, Leicester remains guardian of the king’s remains, reinterred less than 100m from where he was originally buried, in a new tomb in Leicester Cathedral.

Read more about the search for Richard III at the University of Leicester website.

Find out how to visit Leicester Cathedral.

Find out how to visit the King Richard III Visitor Centre.

Gallery

On loan to Leicester Museums & Galleries

Richard III Society

University of Leicester

University of Leicester

University of Leicester Archaeological Services

Leicester Cathedral

Richard III